I talk so much about lenses in class that some of my students must think I’m a closet optometrist. The lenses I refer to, however, are those that we all wear as part of our culture. We can’t help it – being born into a worldview is part of the human experience. From my youngest days I recall learning that the earth is twirling around at a dizzying rate and we are hurtling through space around the sun so fast that my thoughts can’t even keep up. These are lenses. Then we turn to the Bible (or other ancient texts for that matter) and read about the creation of their world. To understand their worldview we need to take our lenses off.

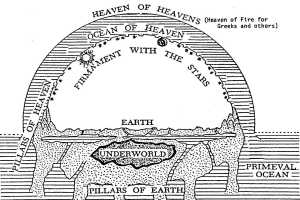

Last night I could see the understanding dawning on some faces in the classroom as I described ancient Israel’s worldview. They were flat-earthers, each and every one. The world that is described in Genesis 1 is flat with an invisible dome over it, a dome that holds back the cosmic waters and provides a living space for the sun, moon, and stars. The flat earth is upheld by pillars that erupt through the surface in the form of mountains, and there is water around all. Genesis 1 does not describe the creation of water; it is already there. You can tell there is water above the dome because it falls on us whenever it rains. Oh yes, and dead people are in Sheol, somewhere under our feet. This is the world that God creates in six days. It is not our world. It was their world.

It is not that the physical world has changed, but perceptions of it have. When I stand outside (this was especially noticeable when I lived in central Illinois), I see the world is flat. I feel no motion – I get sick as a dog swinging my head around too fast, so I would know! The difference is that I understand apparent reality is not the same as physical reality. The writers of Genesis 1 did not anticipate our world, nor did they describe how it came to be. They described the world they knew, a world that does not actually exist. Fundamentalists today claim that the Bible is factual in its description of the creation, and that may be the case. But only if you take your lenses off and admit that the world God created is flat and is covered by a dome. And by the way, it looks like the windows of the sky were left open because it is beginning to snow again.

8 thoughts on “How Flat is Your World?”